Quantum Computing with Neutral Atoms

Programmable arrays of Rydberg atoms

With the rise in our capacity to control and explore synthetic quantum systems, the opportunity to use them to address questions of scientific and industrial interest has attracted the efforts of a large community of researchers. Today, the control of single atoms as well as the tuning of their interactions has been achieved to a high degree in several laboratories. One of the leading architectures for constructing these programmable devices consists in arranging ensembles of individual (trapped) atoms separated by a few micrometers. In order to generate interactions between them, they are excited by a resonant laser field to a Rydberg level, which has a large principal quantum number. At the Rydberg state, the atoms present long lifetimes and large interaction strengths and are briefly called Rydberg atoms.

This page gives brief insight into the concepts behind Pulser and the use of neutral-atom devices for quantum computation and simulation. For more details, see Quantum 4, 327 (2020) for a comprehensive overview of quantum computing with neutral atoms, Nature Physics volume 16, pages132–142(2020) for a review that’s more focused on their use as a quantum simulation, or even M Saffman 2016 J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49 202001.

Implementation and Theoretical Details

Hardware Characteristics

In a nutshell, neutral atom devices feature two main components:

The Register, a group of trapped atoms in a defined (but reconfigurable) configuration. Each atom holds a specific quantum state encoded in specific electronic levels. Usually these are two-level systems and we refer to them as qubits.

The Channels, responsible for manipulating the state of the atoms by addressing specific electronic transitions. These consist most often, but not exclusively, of lasers.

Each Device will impose specific restrictions on these components – they define things like how many atoms a Register can hold and in what configurations they can be arranged in; what channels are available and what values they can reach, among others. For this reason, a Sequence is closely dependent on the Device it is meant to run on and should be created with it in mind from the start.

This Sequence is the central object in Pulser and it consists essentially of a series of Pulses (and other instructions) that are sequentially allocated to channels.

Each Pulse describes, over a finite duration, the modulation of a channel’s output amplitude, detuning and phase. While the phase is constant throughout a pulse, the amplitude and detuning are described by Waveforms, which define these quantities values throughout the pulse.

A pulse sequence and its execution on a given device.

In the animation above, we find an example of a Sequence composed of three channels, each containing different pulses played at specific times. Upon execution, the channels emit this coordinated stream of pulses, which manipulate the state of the atoms in the register.

Now, what is left to know is how these channels manipulate the state the atoms so that we can program them to do meaningful things. To do this, we have to dive into the physics and try to understand the underlying Hamiltonian of our systems.

Driving two-level transitions

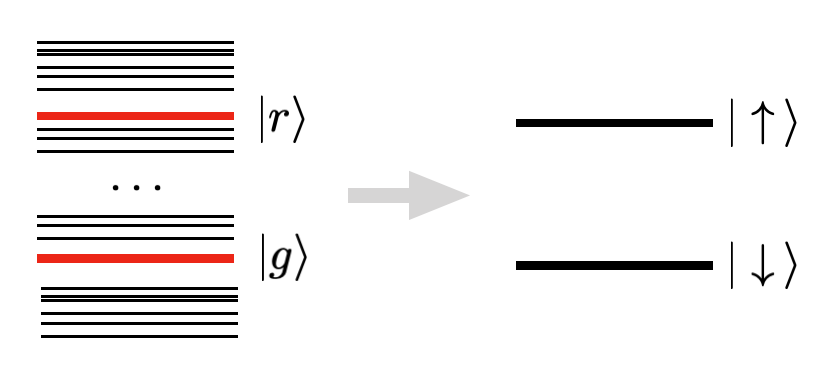

Each channel is tuned such that each of its pulses coherently drives a

specific electronic transition between two energy levels of an atom.

For instance, when addressing the ground-rydberg transition, we have that

our targeted levels are the ground state, \(|g\rangle\), and the Rydberg

state, \(|r\rangle\). These two states can be thought of as the two levels

of a quantum spin.

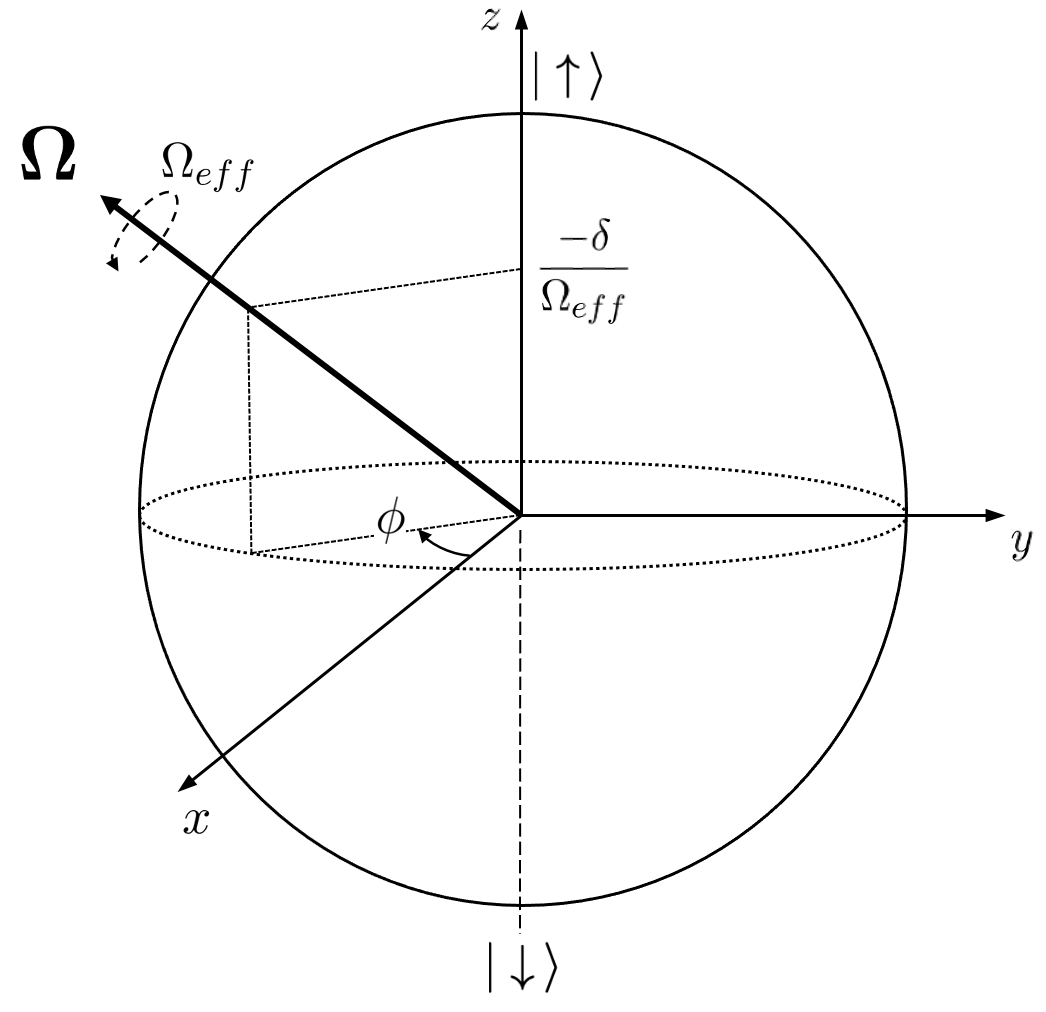

In this system, a pulse acting on an atom \(i\), with Rabi frequency \(\Omega(t)\), detuning \(\delta(t)\) and a fixed phase \(\phi\), will have the Hamiltonian terms:

where \(\sigma^\alpha\) for \(\alpha = x,y,z\) are the Pauli matrices. Alternatively, one can rewrite this term as:

where \(\mathbf{\Omega}(t) = (\Omega(t) \cos(\phi),-\Omega(t) \sin(\phi),-\delta(t))^T\) and \(\boldsymbol{\sigma}\) is the vector of Pauli matrices. In the Bloch sphere representation, for each instant \(t\), this Hamiltonian describes a rotation around the axis \(\mathbf{\Omega}\) with angular velocity \(\Omega_{eff} = |\mathbf{\Omega}| = \sqrt{\Omega^2 + \delta^2}\), as illustrated in the figure below.

Rydberg states

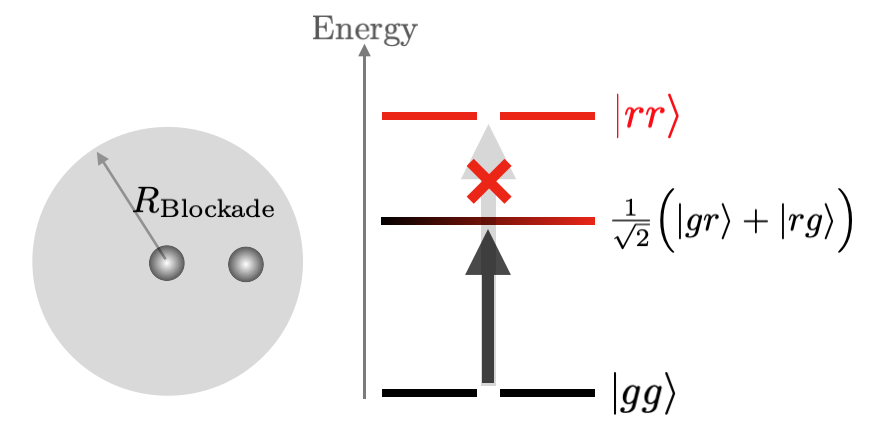

In neutral atom devices, atoms are driven to Rydberg states as a way to make them interact over large distances. The interaction between two atoms at distance \(R\) and at the same Rydberg level is described by the Van der Waals force, which scales as \(R^{-6}\). This interaction can be exploited to create fast and robust quantum gates, using the so-called Rydberg Blockade Effect between them. This effect consists on the shift in energy between the doubly excited Rydberg state of nearby atoms and their ground state, making it non-resonant with an applied laser field coupling the ground and Rydberg levels.

Because of the Rydberg blockade, an atom cannot be excited to the Rydberg level if a nearby atom is already in such state. To represent this interaction as operators in a Hamiltonian, we write them as a penalty for the state in which both atoms are excited:

where \(n = (1+\sigma^z)/2\) is the projector on the Rydberg state, \(U_{ij} \propto R_{ij}^{-6}\) and \(R_{ij}\) is the distance between the atoms \(i\) and \(j\). The proportionality constant is set by the chosen Rydberg level. If the atoms are excited simultaneously, only the entangled state \((|gr\rangle + |rg\rangle)/\sqrt 2\) is obtained.

An entire array of interacting atoms, acted on by the same pulse, can be represented as an Ising-like Hamiltonian:

Digital and Analog Approaches

Analog Approach

In the analog simulation approach, the laser field acts on the entire array of atoms. This creates a global Hamiltonian of the form

Through the continuous manipulation of \(\Omega(t)\) and \(\delta(t)\), one has a very high degree of control over the system’s dynamics and properties. In this way, the analog approach enables the quantum simulation of many-body quantum systems, but also provides novel ways of solving combinatorial problems that can be mapped onto the hamiltonian above.

Digital Approach

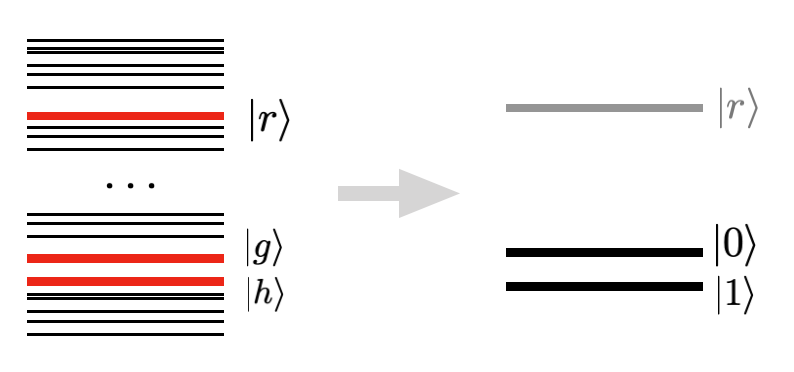

In opposition to the analog approach stands the digital approach, in which

a system’s state evolves through a series of discrete manipulations of its qubits’

states, also known as quantum gates. This is the underlying approach in quantum

circuits and it can be replicated on neutral-atom devices at the pulse-level. To

this extent, the qubit states are encoded in two hyperfine ground states of the

system, named ground, \(|g\rangle\), and hyperfine, \(|h\rangle\). In

Pulser, these states form the digital basis, which is addressed by Raman

channels. In the digital approach, these channels are usually Local, meaning they

target individual qubits instead of the entire system.

Since the Rydberg blockade effect is not present when atoms are in \(|g\rangle\) or \(|h\rangle\), the dynamics of each qubit’s state are just determined by the driving pulses, already illustrated above as rotations on the Bloch sphere. By tuning the parameters of a pulse, we can achieve any arbitrary single-qubit unitary, as is shown in Phase Shifts and Virtual Z gates.

However, without the interaction introduced by the Rydberg blockade effect, it is not possible to do multi-qubit gates. Therefore, the Rydberg level is used ancillarily in order to generate a conditional logic on the atoms by attempting an excitation which will be blocked (or not) depending on the distance and current levels of the involved atoms. This is the key behind the CZ gate, whose implementation is detailed in Control-Z Gate Sequence.